What's the best way to make my personal website?

Kim responds to the most Freqently Asked Question on our Discord. In the start of our new series on getting started online, we take a look at what a website is under the hood, the main ways you can go about it, and the pros and cons of each overall category.

The question we get the most on the Discord is simply “how do I get started with a web presence?” As you might expect, there are a plethora of options out there today making it somehow even more confusing than ever to know where to start.

A lot of the reason it's so confusing is that none of the options out there really tell you what you're getting into, or the rationale behind each option. Much like starting a skin care regimen there just seems to be an absolute ton of steps and products and jargon and hyper-specific marketing that all overlap. It's also a mess of brand recognition and people with very strong very specific opinions.

Rather than start with a discussion of specific platforms then, we will start what we hope to be a series on setting up websites with an overview of the options as overarching categories.

What is a website?

But before that, let's have a think about what a website actually is. Websites have gone from being something very simple in the 90s – a way to publish hyperlinked text documents with a little styling – to being the primary delivery mechanism for almost all of our entire day-to-day lives.

Underneath it all though there are three basic components:

HTML files, which contain the actual text content of the website, with it's distinctive <strong>angle bracket tags</strong>. These tell the browser what the content is: in this case, it emphasises the text. HTML is like the screenplay for your website: it describes everything that happens, but how to interpret it is left to other tools. If you've ever styled a MySpace or LiveJournal blog, or used BBCode on a web forum, you're on the right level. A webpage is typically one of these, a website is multiple connected together.

CSS files, which tell the browser how to display the HTML files. This is where you tell it what font and how big things are, how the page columns should work, and what colour everything is. It's also responsible for changing at various screen sizes so it looks different on phone and desktop.

JavaScript files, which handle non-trivial interactive elements. HTML handles a lot nowadays but you typically need JavaScript to handle ‘app-like’ behaviour: anything that changes without the page reloading such as games or drag and drop interfaces. Note that most personal sites simply don't need JavaScript, or just use it for one thing such as toggling a navigation.

These three elements can then load any other media files such as images, music or video.

In reality the boundaries between these are fuzzy and ever-changing. While it's generally frowned upon, you can put CSS directly in your HTML rather than its own files. You can do a lot of animation with CSS now that used to only be possible with JavaScript. People manage their HTML inside JavaScript files. HTML adds new things to the spec every day that replace things that we used to need JavaScript for like the <details> tag. Trends on this change regularly and it can be tough to keep up with. On a bread-and-butter level, all you need to remember is that these three elements make up everything you experience in a browser whether it be Facebook or your first Hello World website, roughly representing the content, styling, and interactivity.

What is a web server?

Whatever route you choose your website eventually needs to live on a web server. A server is basically just someone else's computer, in a data centre, with special software running on it for hosting websites. This is because when someone types in the website name in the browser you want it going to a dedicated computer just for the purpose and not your personal laptop. The mechanics of this are quite different depending on which route you choose.

So what ways should I consider?

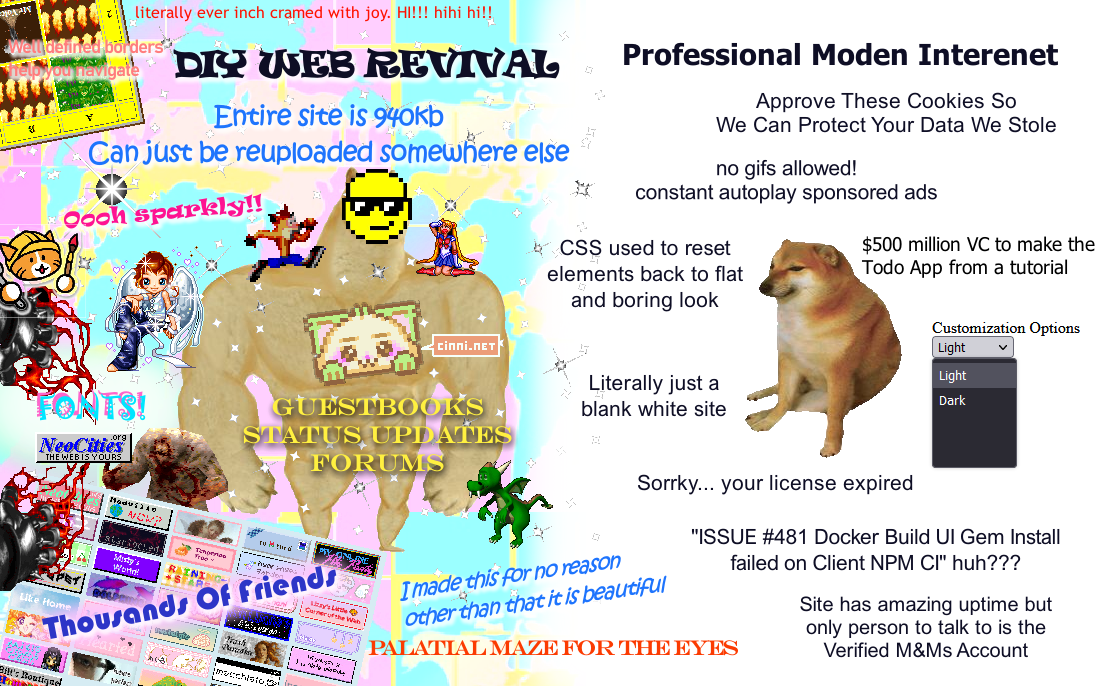

Just write HTML files and upload them

Remember seeing someone open up a notepad.exe document, writing some html and uploading it to a web server? Well you can still do that! If you spend a day or two learning HTML you'll learn some really good core skills that will probably make working with the web a lot easier. You can then upload the html file you make to a range of free services such as Neocities, Nekoweb or yay.boo.

Pros: free, teaches you vital core skills, as DIY as it gets, incredibly minimal file size, portable, web 1.0 aesthetic.

Cons: html isn't nice to write content in, doesn't scale well, web 1.0 aesthetic, overly manual.

Static site generators

Static site generators are a firm favourite at GFSC. The GFSC Studio website is made with one, and we have made them for a bunch of clients. A static site generator is essentially a script that takes in a bunch of different text and image files and spits out a website in plain HTML and CSS that can then be uploaded to a range of services.

Rather than have each page be completely unique, you create a set of templates for your site or use one of many off-the-shelf themes. These templates will be for things like a blog or news post, a static content page (about / contact), or an author bio page. As the templates are just HTML and CSS you have maximum control over them which makes it perfect for anyone who likes to fiddle.

Instead of writing your content in HTML you generally write in Markdown, which is a plain text format supported in a lot of places now that allows you to do the basics of laying out headings and bold, italics and images, makes paragraphs work without those nasty <p> tags and generally is a lot nicer to work with. These Markdown files get converted to HTML and squirted into the templates when the static site generator is run.

The enormous advantage of a static site is that your website is just a bunch of files in a folder on your computer. This means you can use all your normal operating system tools to manage it such as image resizing, text editors of your choice, file browsers, etc. In doing this it means you always have a copy of your website and can experiment with changes locally before deploying them to your web server.

The downside is that you do need to get your feet wet and often this means installing a bunch of developer stuff on your computer. If you've ever touched a programming language before there's a good chance there's a static site generator for it, but if not it can be a bit of a faff learning how to get a development environment up.

For deployment you really need to learn Git. Git is a version control system but it's also a way to transfer files to a remote server on a service like GitHub, Cloudflare or Netlify. Learning Git opens up so much of the indieweb ecosystem to you so it's really good to learn, and while there are tools like GitHub Desktop to make it easier for you it's good to know what's happening under the hood.

If this doesn't put you off then there is a wide range of static sites all with their own pros and cons. Very briefly here are a few recommendations and the language they are written in in case you already know a bit of one of them:

- Hugo (Go). Pros: runs from one static file so you don't need to install a load of developer dependancies, very flexible, has built in image resizing. Cons: templating language is terrible.

- Eleventy / 11ty (JavaScript). Supposed to be really good but I've not tried it yet!

- Jekyll (Ruby). One of the original ones and works natively on GitHub Pages. Ruby is a pain to set up locally if you are not already au fait with it, and it lacks features compared to some more modern ones. However, the templating language is really simple to work with.

- Quartz (JavaScript). Good for specifically “digital garden” style sites.

Pros: free, portable (i.e. no vendor lockin), very archive-friendly, highly customisable, use all your current operating system tools, easy for your developer friends to help you out.

Cons: you probably have to learn git, posting friction can be higher than something with a dedicated post editing interface, you probably need to install a load of developer stuff on your computer and type a bunch of things into the terminal.

Commercial website builders

At the opposite end of the spectrum with almost the opposite pros and cons are commercial website builders. There are a lot of these for a whole range of use cases which are not always apparent. The good part of them is they make it very very quick to publish something online. Bad news though – you are now a customer – the vendor will most likely attempt to lock you in, forever, and probably extract a monthly fee from you somewhere along the way with extra features behind behind further price rises.

Even if these conditions seem OK now just remember you have no control over what happens to it in the future via the now-well-documented process of Enshittification, the entire platform could be bought by someone far worse tomorrow, or it could be retired entirely. You're probably also sharing all your visitor's data with 700 or so of the proprietor's closest friends, and it's almost definately getting fed into LLM training.

Sometimes the job has to get done though, and there are deffo some better than others. While I wouldn't pick them for me I think commercial builders make sense in work contexts (i.e. someone else is paying), or for time-limited projects with an end date.

Some examples are:

- Google Sites gets overlooked a lot and I'm not sure why – if you have a Workspace account it's included in that. I think the themes are not the prettiest but it's very functional and links well to other GSuite tools.

- Webflow is the current hype for smaller budget websites. I've seen some really nice websites in it but it's one of the more expensive ones with plans starting at $14/mo at time of writing.

- Squarespace has been around a while and seems pretty reliable. It has decent SEO and events management (and integrates with PlaceCal as a result) -- we've found it in use a lot by London venues. It's currently similarly priced to Webflow starting at £12/mo.

- Weebly is a bit cheaper starting at £5/month. It seems fine.

- mmm.page is a bit of a fun option. I'm worried about the accessibility but it's nice to mess about with and charges $6-12 month.

The only one I would strongly suggest against is Israeli company Wix, which has an active consumer boycott against it supported by BDS. (If you'd like help migrating off Wix please do join our Discord where people will be glad to help).

Pros: instantly get going, good professional out-the-box templates, vendor tech support exists, can have very sophisticated features that would be expensive to build yourself, don't have to touch any code, don't have to think about servers.

Cons: monthly costs which go up as you add more features, you have no control over the platform, accessibility can be poor, rife with user tracking, it can be very hard to export your content, using custom code can be impossible, archiving is very, very hard.

Self-hosted open source blogs

If you want the power of an app but don't want to touch any code you can look into using something self hosted and open source. All of these are relatively complex web applications that run on a web server and require a database. Your content is stored in a database instead of HTML files, typically something like MySQL. What can make it confusing is that layouts and configuration are also stored in the database. The benefit is that you can have a nice editing interface and more easily collaborate with a team.

Perhaps the biggest downside of this is that the server then becomes another thing you have to worry about and install updates on that you're paying a monthly fee for. In our static site category there is nothing to hack or maintain – it's just simple files in a directory. In the case of something self hosted you do need to know what you're getting into, have a backup strategy, and ideally have a friend to help out. They can therefore be a lot quicker to get up and running with at the cost of being more of a pain and liability to maintain later.

- WordPress is the Big Name here but I've never got on with it personally. It kinda does everything in the way that Microsoft Word does everything: ugly and semi-functionally. Most sites I find in use are just a poorly-optimised mess of plugins and with half implemented themes. WordPress developers generally tell me it works if you spend a few hundred quid on X, Y and Z paid plugins but that seems to just highlight the fundamentally flawed infrastructure of it to me. Anyway – it's probably fine if you get someone who knows what they are doing to set it up for you.

- Ghost (referral link, gives you a discount on paid Ghost plans) is what powers this blog and is my current fav by far. It was set up by ex-WordPress developers who wanted to make “just a blog”. It has email newsletter features built in and is probably closest to Substack in terms of functionality. The main downside is hosting it. Their official Ghost Pro offer is a good option if the limits don't bother you, but if they do, self hosting is a pain. On the plus side it has ActivityPub integration now so if you know what this is I think it's an extremely good option if you can get over this hump.

- Drupal is what I used to specialise in and I've not used it for a while but to me it does everything WordPress does, but better, with a proper stable ecosystem – you won't be reaching for your wallet. It has a wide range of modules that are well scoped and work well together. It deffo has a steeper learning curve though and a lot of people bounce of it for this reason.

- Write Freely is a newish one I've not tested yet but looks great for a very simple blog and also has ActivityPub integration.

Pros: all the ease of use benefit of commercial website builders with no risk of enshittification, you're in control of your data.

Cons: monthly server hosting costs, can be a pain to set up without a friend to help, doesn't archive well, harder to back up, needs ongoing maintanance.

“Everything” apps “publish to web” option

As mentioned in the intro, there are a lot of ways to display HTML on the web and one of the most versitile can be so-called "everything" apps like Notion, Coda or open source and decentralised upstart Anytype. In all of those you build a page in the tool then use a "publish to web" option, which will give a link like this.

Pros: might be a tool you're already using so you're more likely to update it, good editors, loads of features, pretty instant to get going.

Cons: monthly costs, can be very slow to load, can feel really unprofessional, usually only one theme, SEO is awful, hard to migrate off.

Wildcard choices

Want some other options now we're loosened up? OK let's go!

- Google Doc/Sheets: just publish a Google Doc! (file -> share -> publish to web).

- leaflet.pub: a kind of bluesky-integrated google doc but make it simple idea.

- AirTable (referral link, gives us $10 credit): nocode database solution good for structured data with an examples website. See also Baserow and Grist.

- Downpour: phone app that lets you take photographs and stich them together.

- Pastebin: dust off your ascii art and just paste in some plain text

- omg.lol: tiny personal site builder.

Conclusion

Long story short, there are a lot of ways to publish things on the internet.

Most of the time when people are asking me what's best they are typically making a site for themself, are not exactly flush with money, care about customising things themselves, and don't mind doing a bit of self-learning. In these cases I recommend learning a static site generator.

If one of those things is not true: say you have a bit more money, are working on a team, have less time, or don't want to expect anyone writing for it to have to learn HTML and git, then I'd go with a managed open-source blog platform. Just be aware this is a thing that is going to take ongoing maintanance and care.

Typically I'd only recommend a commercial website builder for professional settings where there is a budget set aside for it and the website will have many different matainers, or where you need an out-the-box ecommerce solution (although ecommerce is for a blog post another day). While they are the easiest to get going with this is a central part of their business plan and it can be almost impossible to extricate yourself later.

If you're in a huge hurry and it has to be up tomorrow I'd deffo have a think about the wildcard options and ask yourself what really has to be up tomorrow – can a domain name linking to a Google Doc do the job?

Did we forget your favourite platform? Agree or disagree with our summary? Which would you like us to do a deeper dive into first? Let us know in the comments!

Comments ()